NEWSLETTER

|

Through the Years in China: A Story of “Intersections” By Joan Kaufman

Since the LAFF event in March at the newly renovated Ford Foundation building, I’ve been thinking of the many ways the Foundation influenced my career before and after my stint as a program officer in the China Office, and all the intersections of people, places and issues that came together and formed a trajectory for the social justice issues I have worked on.

Those intersections have been China, health and women’s rights and a story that began in 1980. I have lived and worked in China three different times since then for more than 15 years, with my time as a Foundation program officer right in the middle of an arc of work focused on advancing justice on reproductive health and rights, HIV/AIDS and women’s rights.

With two degrees in China Studies, a master’s degree in public health and a newly published book on the China population program based on my master’s thesis, A Billion and Counting, I was hired in 1980 by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) as its first international program officer for the newly opened UN office in China. Deng Xiaoping had invited the UN to China in 1979 to assist with the “Four Modernizations” and one of them was to quadruple GDP by the year 2000. So the government needed to know the precise population and UNFPA was invited in to help with the census and train demographers, among other things.

My initial contact with the Ford Foundation came when I flew to New York from Berkeley for the interviews and was promptly introduced to Bud Harkavy of Ford, who was the “go to” person for global population issues and a close collaborator with UNFPA.

I spent four years with UNFPA in China until 1984 and made deep friendships with many Chinese academics and officials that continue to this day. China then was nothing like what it is today, and I often look back at those days in disbelief at the subsequent transformation of the country, remembering clearly how challenging it was to live there as a Chinese-speaking American working for the UN (obviously a spy!).

I also recall the sigh of relief and beginnings of change after the “Gang of Four” trial during my first year there. I have witnessed the remarkable transformation of China in one generation, and that perspective has been important in understanding the place in both more open and more challenging times.

When I left UNFPA in 1984, I began a deferred doctorate at the Harvard University School of Public Health and eventually returned to China in 1987 to conduct dissertation research on the one-child population policy with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, which was interested in getting a foot in the door to work on population issues there. It was at Harvard that my contacts with Ford deepened.

Lincoln Chen had just left India as the Foundation’s representative and arrived at Harvard as my department chair, where he joined my dissertation committee. This was the late 1980s and the global HIV/AIDS epidemic was gaining steam. Lincoln launched a new global initiative at the department, “The AIDS and Reproductive Health Network”, which I became deeply involved with, spending several years immersed in the AIDS response in Africa, Mexico and Thailand and serving as a consultant for the newly launched WHO Global Program on AIDS. When Peter Geithner, Lincoln’s close colleague and friend who was the Foundation’s first China representative, approached him around 1990, two years after the Foundation opened its China office, about exploring whether the China office should add a reproductive health program portfolio, I began my relationship with Ford.

The Foundation, under Jose Barzelatto, was expanding its global work on reproductive health and rights in the lead-up to two big UN-sponsored conferences: the ICPD (International Conference on Population and Development, which took place every ten years) and the Beijing Women’s Conference (Fourth World Conference on Women). The Foundation was helping to shape a new global women’s rights and sexual rights framework to replace the focus on population control, which often had been pursued at women’s expense. Peter contracted with me to do a year-long needs assessment for the China office, during which time I got to know Peter and the staff.

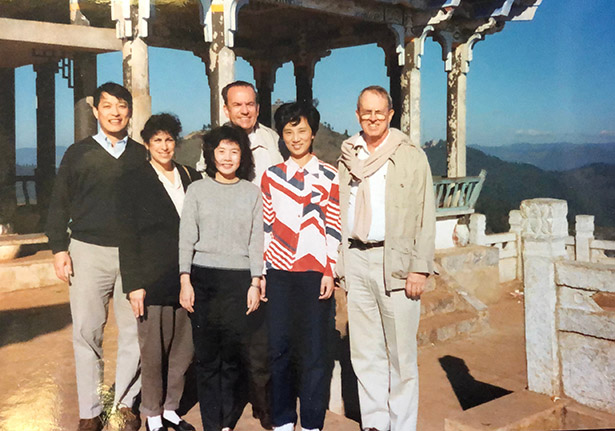

One of my fondest memories is the visit that Peter, Lincoln, Jose and I made to Yunnan along with Zhang Ye, Peter’s assistant and his “right hand woman” in the office, who later directed the Asia Foundation’s China Office and even later worked with Lincoln at the China Medical Board. The new program began in 1991 and I led several Ford projects in Yunnan during that first phase.

My connection became official when I joined the office as the second program officer for gender and reproductive health after the Beijing Women’s Conference in 1995 and inherited an incredible portfolio from my predecessor, Mary Ann Burris, that helped shape the burgeoning Chinese feminist movement.

In the lead-up to the Beijing Women’s Conference, the office helped establish a group of women’s NGOs, supported a group of women’s studies scholars and supported government initiatives focused on women’s legal and social rights. These groups and individuals were the main partners and counterparts for global organizations that attended the NGO Forum and cemented transnational civil society relationships that have flourished to this day.

After I arrived, I continued to work with these groups to advance work on women’s rights, such as domestic violence and migrant labor rights, and expanded the portfolio to address the reproductive rights challenges of the population policy and the emerging HIV/AIDS epidemic. Subsequent program officers (Eve Lee, then Susie Jolly) continued and expanded some of the earlier work and especially built out the work on sexuality and sexual rights initially as part of a Foundation global “Big Bet”, while moving the portfolio into other important directions before it ended several years ago.

The Ford Foundation played a truly unique and critical role in China in the 1990’s at a time when no other private foundation was on the ground. Unlike the UN and the bilaterals that could only partner with government agencies, the Foundation made grants directly to a wide range of actors. We partnered with academics, NGOs, local government organizations and mission-driven individuals who were promoting social change.

I was drawn deeply, as I am today, to the social justice agenda that was community oriented with a focus on local voice and participation in governance through NGOs or local mechanisms, and the ability to link those to national and local policy change. These are the issues I continued to work on after leaving the Foundation in 2001, both in my academic research, in particular the Global Gender and Health Equity Network and the Community Based Counseling for Chinese AIDS Orphans project, and in work with other mission- driven organizations, including the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, where I trained clinical trial communities about the research process and their rights.

In an article I did with the China portfolio’s three other program officers, Mary Ann, Eve and Susie, for a volume on Philanthropy for Health in China, edited by Lincoln Chen, Tony Saich and Jennifer Ryan with a forward by Peter Geithner and published in 2014, I reviewed some of the impacts of the Foundation’s reproductive health portfolio in China over its 30 years. Those impacts were far-reaching and span many issues. Just one, the China Domestic Violence Network, funded in the late 1990s, moved domestic violence from a personal family matter that the police refused to intervene in to a new national law that also saw the Foundation’s China office’s law program providing crucial support for training judges and legal organizations to defend women.

Early grantees, both individuals and their organizations who started working with us around the time of the Beijing Women’s Conference, coalesced into the network and moved those issues forward, many while leading other important initiatives, such as the Women’s Media Project and the Women’s Law Center.

Similarly, Foundation support for a Quality of Care initiative with the national family planning commission in the 1990s helped transform the coercive family planning program into one that paid attention to contraceptive choice and rights, began a long overdue assessment of the negative demographic and social impacts of the program, and eventually helped lead to the end of the one-child policy.

The portfolio’s work on sexual rights, in conjunction with the worldwide initiative, opened the space for LGBTQ rights in China. The work on HIV/AIDS built a vibrant NGO community that has continued to partner with government on the response and helped institute global norms about community engagement in governance of the AIDS response.

The key to many of these long-term initiatives that spanned the life of the portfolio were a set of local and national champions supported by the Foundation who advocated and liaised with government to change policy. Among these was China’s leading bioethicist from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Qiu Renzong, who we worked with from the earliest days of the program and who organized, advocated and influenced policy on such varied issues as feminism and women’s rights, LGBTQ rights, the rights of HIV infected persons and coercion in the family planning program.

The Foundation also provided core funding to the academic sexuality research field and linked it to gender studies, the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and youth sexuality health and rights initiatives, and to global actors doing the same.

These China programs were not working in isolation. The Foundation in New York and its many field offices during the years I worked in China were funding similar work and supporting global networks through coordinated grant making that connected the global dots to inspire and mobilize a global movement for change. Helping to build these transnational networks has always been a critical contribution of the Foundation in China and elsewhere. Ford’s reproductive health program built global and regional networks and joined with other like-minded donors at that time, such as the McArthur Foundation.

After I left the Foundation in 2001, I returned to Harvard as a Radcliffe Fellow for a year, writing about the impact of the Beijing Women’s Conference on China’s emerging feminist movement and developing a new initiative. I began the AIDS Public Policy Program at Harvard’s Kennedy School aimed at mobilizing an urgent response to the AIDS epidemic in China, in partnership with Tsinghua University.

It was clear that significant policy and governance changes were needed to move the needle on China’s AIDS epidemic. Foundation colleagues surrounded me. I worked closely with Tony Saich, a former China representative who had created the Chinese Leaders in Development program, which also partnered with Tsinghua University at that time. A few years into it, a colleague from the Foundation’s Vietnam Office, Lisa Messersmith, joined me to expand the AIDS Public Policy Program to Vietnam using our assembled faculty and curriculum.

During those years, I was also affiliated with Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management. To my delight, the Heller School was the home of the second highest number of Ford Foundation International Fellows, a program that I worked on in China when it began. It was a delight to teach those scholars and host additional scholars funded by the China Medical Board, led then by Lincoln Chen.

And, to my great enjoyment, I got to work with Peter Geithner again. Peter was connected to Harvard in numerous ways, many focused on China and philanthropy, and he was also serving as a senior advisor to Lincoln and the China Medical Board. Peter roped me into helping organize the Boston LAFF chapter and together we pulled together the many Boston-based Foundation colleagues and organized quite a few fun gatherings. Peter also mobilized a Beijing LAFF Chapter, of which I am an active member and which has been a wonderful way to keep former and current China staff and program officers connected.

I moved back to China in 2012 as the director of the new Columbia Global Center in Beijing, one of eight established by Columbia University to expand its global footprint. One of the highlights of that stint was working with the Foundation’s China Office to host a series of roundtables and events on “Beijing + 20”, commemorating the twentieth anniversary of the 1995 Beijing Women’s Conference and taking stock of the state of women’s rights in China, together with many former and current Foundation grantees and other experts, younger and older.

I moved to my current position in 2016 as the Academic Director for the new Schwarzman Scholars Program, modeled on the Rhodes Scholars Program at Oxford but based in China at Tsinghua University and aimed at training future global leaders to bridge China and the World on global affairs, never more important than at this difficult time in US-China relations and reconfigurations in the world order.

I work with many former grantees at Tsinghua, including our Schwarzman College’s very own Dean, Xue Lan, a longtime colleague from my years with Ford China, the Kennedy School and the Columbia Global Center. I am based in New York but spend a lot of time in China, truly my second home after all these years. I don’t know what the future holds, but I am sure it will keep circling back to the many inspiring Foundation colleagues and friends who continue to change the world for the better and with whom I have intersected over a very interesting career.

Joan Kaufman is Senior Director for Academic Programs, Schwarzman Scholars, and a lecturer in Global Health and Social Medicine at the Harvard Medical School.

|