NEWSLETTER

|

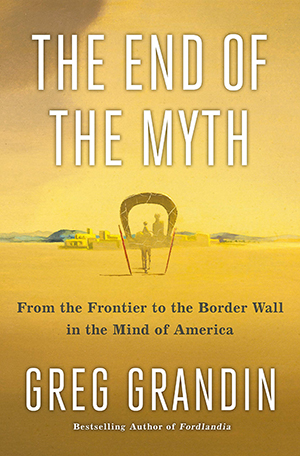

Book Review: A “Compelling Context” for “Profound Pessimism” By Thomas Seessel

This book explores how the concept of frontier has dominated American ideology and fueled our ascent as a super power. It puts a critical spotlight on the shifting meaning of “frontier” throughout our history: from the wilderness to global influence to Vietnam and to outer space.

And in a searing conclusion drawn from his timely study of a singular American myth, Grandin expresses profound pessimism about America’s future. His views are molded largely by our having resisted the adoption of a social democracy, and quashed development of a critical, resilient and progressive citizenry. Instead, Grandin finds, we have adopted “a conspiratorial nihilism, rejecting reason and dreading change.… Factionalism congealed and won a national election.”

The book won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction, which praised it as “a sweeping and beautifully written book that probes the American myth of boundless expansion and provides a compelling context for thinking about the current political moment.”

The author, Greg Grandin, a Yale history professor, passionately and eloquently portrays how “the presence of a frontier has allowed the United States to avoid a true reckoning” with iniquities such as slavery, decimation of Indigenous People, racism and gross inequality.

Grandin tells this story in chronological order, vividly and unforgivingly, beginning with the formation of the country and ending with the Trump border wall. Grandin devotes a chapter to each of the major eras: Jacksonian democracy, annexation of Texas, the Mexican War, the Civil War, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, the Spanish-American War, the World Wars, the Depression and New Deal, the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War (which supporters and critics alike described as yet another frontier war), Reagan and the New Right, Clinton’s globalism, the mid-East wars and Trump’s closing of the frontier with a retreat from internationalism. Grandin finds that, in the end, “Instead of peace, there’s endless war.”

The End of the Myth details how subjugation or eradication of Native Peoples has been a mission since Revolutionary times. Thomas Jefferson coupled this cause with the pursuit of freedom, believing that the “final consolidation” of American liberty would come only when the continent was occupied by white, English-speaking people with neither “blot nor mixture”. (After the Louisiana Purchase, Jefferson established government trading houses that ensnared Native Peoples in predatory debt intended to result in default and forfeiture of land given as collateral.)

The 1783 Treaty of Paris, ending the Revolutionary War, set the new nation’s western boundary at the eastern side of the Mississippi River, with Spanish territory on the opposite shore. This limit was soon breached when American boats moored on the western bank, offering the justification that pre-steam vessels needed to tack from side to side in order to navigate upstream. Thereafter the boundary was pushed westward by various means, including purchase, but supplemented by encroachment, chicanery, confiscation, vigilantism and war.

Grandin recounts a colorful episode in the pre-Presidential career of Andrew Jackson, who possessed slaves and amassed significant fees processing the claims of land taken from Native Americans. The incident, which Grandin returns to frequently as a crystallization of his thesis, occurred in 1811, when Jackson was moving a slave “coffle”, or procession, along the Natchez Trace, an ancient Indian road parallel to the Mississippi River that traversed Chickasaw and Choctaw lands, which were ostensibly protected by U.S. treaty.

Jackson was stopped by a federal Indian agent checking the passports of travelers passing through. When asked for his papers, Jackson is said to have replied, “Yes, sir, I always carry mine with me,” brandishing the U.S. Constitution, which is “sufficient passport to take me where ever my business leads me.”

Mexico is a major focus of The End of the Myth. After the Louisiana Purchase from France, in 1803, the largest remaining obstacle to American ownership of the continent was Mexico, whose territory extended to California. Our 1848 war against Mexico, undertaken in the name of “manifest destiny”, resulted in the addition of a huge area to our domain, comprising roughly two-thirds the amount of land in the Louisiana Purchase.

The credo of advancing liberty through expansion was embedded in the American narrative by historian Frederick Jackson Turner in an 1893 paper maintaining that the availability of unsettled land throughout much of American history was the most important factor determining national development.

The author has mixed feelings about the lasting impact of Turner’s thesis. Grandin agrees that frontier and individualism persist as powerful metaphors for American history, but is troubled that the concept has been distorted to justify opposition to governmental restraints on behavior and establishment of a reliable social safety net.

Libertarian and right-wing political mythology embrace rugged individualism and disparage the role of government. However, as Grandin notes, Turner recognized that government made settlement possible, writing in 1893 that “The West of our day relies on national government because government came before the settler, and gave him land [and] arranged his transportation.”

Grandin, lamenting the lack of social democracy, points out that, contrary to the mythology of individualism, the West has always been “the domain of large-scale power, of highly capitalized speculators, businesses, railroads, agriculture and mining.”

Grandin writes that extension of the frontier westward, after the Mexican and Civil Wars, was led by a new alliance of “slavers and settlers under a banner of freedom defined as freedom from restraint….[and] the virtuous commonweal was defined as expansion….” Sons of the Confederate “Lost Cause” found new purpose in joining with their former enemies in pursuit of Manifest Destiny. Grandin bitingly refers to this as the southern veterans’ “rehabilitation program”.

Grandin argues that the U.S. provoked the Spanish-American War as a means of creating new frontiers outside the continent. Woodrow Wilson said that, as a result of this war, “We made new frontiers for ourselves beyond the seas.” Turner, who lived until 1932, described the post-1898 United States as having become an “imperial republic”.

Grandin returns frequently, and caustically, to the subject of our changing relationship with Mexico. He writes that, after the Civil War, American corporations and individuals dispossessed long-term inhabitants of the newly-acquired U.S. territory, formerly a part of Mexico, of a “massive amount of property”.

(He misleadingly implies that, south of the border, U.S. corporations confiscated large tracts of Yaqui Tribe land. This actually was the doing of the Mexican government in pursuit of its policy to convert small land holdings into large mining and agricultural uses. Many of these Mexican government takings ultimately ended up in the hands of such U.S. corporations as Hearst, Cargill and Phelps Dodge.)

The trade treaty known as NAFTA was promoted by President Clinton, who said that the “global economy is our new frontier [and NAFTA] is the moral equivalent of the frontier in the nineteenth century.” Grandin details the treaty’s cascading disastrous results for Mexico: He writes that Mexico lost nearly two million agricultural jobs as a result of competition from the highly subsidized U.S. agricultural industry.

Grandin devotes a great deal of attention to Clinton’s two terms, acerbically detailing his retreat from the Democratic base as he championed the benefits of NAFTA and globalism. Grandin asserts that Clinton’s subliminal message was that “global competition would discipline the black underclass and help the Democratic Party break its dependence on groups like the Congressional Black Caucus [which opposed the treaty].”

Reagan’s 1980s’ wars in Central America, followed by the war on drugs and NAFTA, spurred migration northward. Illegal border crossings grew and became an increasingly contentious political issue, leading to ever-harsher attempts to stem the flow. By 2016, Grandin says, the U.S. was spending more on border and immigration enforcement than on all other federal law enforcement agencies combined, including the FBI.

The first portion of the border wall was built in 1909, and has been augmented sporadically ever since, most often as an appeasement to immigration opponents who insist on securing the border before immigration reform can be discussed. The wall was a Presidential campaign issue for the first time in 1980, when candidate Reagan, contrary to the portrayal of his policies as enunciated by Trump, opposed President Carter’s proposal to construct additional segments. After he was in office, Reagan said that “God made Mexico and the United States neighbors, but it is our duty and the duty of generations yet to come to make sure that we remain friends.”

Grandin gives scant attention to Barack Obama, dismissing his eight years in office as a futile effort to “reach… for a center that no longer existed, that he seemed to think he could reconstitute by the power of his rhetoric and the infiniteness of his patience.”

The book maintains that Trump’s promotion of the border wall with Mexico symbolically marks the end of American expansion: “What distinguishes earlier racist presidents like Jackson and Wilson from Trump…. is that they were in office during the upswing of America’s moving out in the world, when domestic political polarization could be stanched and the country held together…by the promise of endless growth. Trumpism is extremism turned inward, all-consuming and self-devouring.”

The End of the Myth occasionally drifts into overstatement and confusing metaphors. It seems at times that, in his outrage, Grandin stretches the evidence to fit his ideas. Surely NAFTA, as one example, has produced some benefits that are not mentioned. The immigrant share of our population grew from 4.7 percent in 1970 to 13.7 percent in 2017. And Mexicans made up about a quarter—about 11 million people—of all immigrants living in the U.S. in 2017.

The Covid-19 pandemic occurred after the book was published, but the most incisive critiques of our response echo Grandin’s bleak outlook. An article in the September 2020 Atlantic magazine, for example, says that the Covid-19 “debacle has also touched—and implicated—nearly every other facet of American society: its shortsighted leadership, its disregard for expertise, its racial inequities,… and its fealty to a dangerous strain of individualism.”

Tom Seessel was a program officer in the Ford Foundation’s Urban and Metropolitan office from 1970 to 1974, and a consultant in the Office of the President from 2002 to 2009.

|