NEWSLETTER

|

Ford’s Records an Integral Part of the Rockefeller Archive Center

By Lee Hiltzik

The author is Assistant Director and Head of Donor Relations and Collection Development at the Rockefeller Archive Center. This article was written especially for The LAFF Society newsletter.

Driving up to Hillcrest, once the country home of the late Martha Baird Rockefeller on the grounds of the Rockefeller family estate in New York’s Westchester County, is no longer the social call on the widow of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., that it once was for many. Rather, it is now a purposeful visit to the Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), a focal point for historical research of the various realms of philanthropy.

Perched atop a hill, with a grand view of the Hudson River (though from its top floor, in winter only), the house is the physical marker for the archival vaults that lie in its sub-basements. The Center embodies a vision of the importance of preserving the story of philanthropic work and making that documentation available to a broad research community.

While the records of the Ford Foundation and those of its officers and administrators are a relatively recent addition to the RAC, they are a vital component of this history, including newsletters and correspondence of the LAFF Society.

The official founding of the Rockefeller Archive Center dates to 1974, but its history begins in the 1950s when advisors to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., began conversations about the importance of preserving the records of his personal philanthropy and family history. Part of this discussion grew out of the historic preservation movement that was solidifying at that time and, partially, was a function of the voluminous quantities of materials being collected at the family office in Room 5600 at Rockefeller Center.

By the 1960s, both the Rockefeller Foundation and Rockefeller University had initiated archives programs. JDR, Jr., had passed away but his sons, known as the “Brothers Generation”, became involved with discussions about creating a joint archive for the various Rockefeller entities, by then including the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, their own foundation.

While discussions to construct a joint archive continued for many years, a breakthrough occurred following the passing of Martha Baird Rockefeller in 1971. The decision was made then to convert her country home to a new archival research center, and to construct the archival vaults into the bedrock below the house. This new entity, now officially the Rockefeller Archive Center, was founded in 1974 and opened its doors to scholarly research the next year.

The RAC’s founding institutions recognized immediately that the decision to open their records to outside access would attract widespread interest, and that the growing and changing impact of philanthropy on innumerable aspects of modern life would be of great interest to scholars studying wide-ranging disciplines. Of course, the founders realized that some individuals would seek to uncover conspiracies and rummage through closets for all sorts of skeletons, but there was an overriding faith that interest in the collections would provide a positive, edifying contribution to knowledge—and they were right. (continued below)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

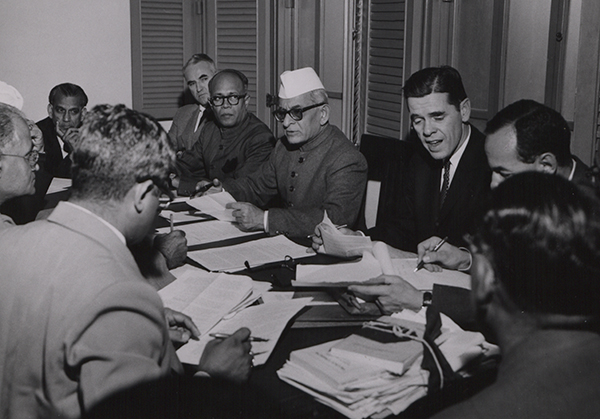

The history of the Ford Foundation is being shaped through a voluminous trove of documents collected at the Rockefeller Archive Center—and through a great many pictures.

Much of the material is clearly marked with each document’s purpose, date and participants, but many of the pictures are not.

A few of those photographs are re-printed here with what information is available to identify them, if there is any at all. We will print more pictures in future issues, hoping that LAFF’s members can provide additional identification to add to the accumulating history of the Foundation.

Information on the people pictured here and the dates can be sent to John LaHoud, editor of the newsletter, at jlahoud25@hotmail.com

More than 8,000 people have come to the Center to conduct research. They avail themselves of a current collection of 120 million pages of documents, 18,000 reels of microfilm, 5,000 films, close to 1,000,000 photographs, 15,000 audio-visual items, 6,000 architectural drawings, maps, and posters, and 45 terabytes of electronic data.

In addition to the scholars who conduct their studies in the Center’s reading rooms, many thousands of others conduct offsite research by requesting copies of specific documents or otherwise engage with our archivists. In recent years, on average, our archival staff has handled almost 2,000 research requests annually.

The majority of our researchers are connected with academe: professors, professors emeriti, graduate students and undergraduates. High school students come to RAC occasionally when they are looking for primary source materials for their papers, and even grade school students, with their parents, who are working on National History Day projects. Our researchers also include architects, documentary filmmakers, landscape architects, genealogists, museum and exhibit curators, and journalists.

The Center defines very broadly what constitutes a bona fide researcher. We do not require letters of introduction or other official documentation. If a person can articulate the parameters of a research project and, as part of a conversation with an archivist, explain how the archival documents in our holdings will benefit his or her work, then the researcher is welcome to pursue his or her study in the open records at the Center.

Almost immediately upon opening the archives of the Rockefeller University, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and the Rockefeller Family, the Center began collecting a wide variety of papers of other foundations either created by or significantly funded by the Rockefeller family. This decision broadened the holdings of the Center to include the records of such organizations as the Asia Society, the Population Council and the Downtown Lower Manhattan Association.

We also began receiving manuscript collections, that is, the personal papers of the officers and administrators who worked within these institutions. These actions greatly deepened and broadened the content holdings of the archives in many far-flung fields, such as scientific research, public health, New York history and cultural history.

The next step in expanding the archives followed in the mid-1980s, when the Governing Council of the Center made a strategic decision to incorporate archival collections of non-Rockefeller-related entities. The archives of the Commonwealth Fund and the Russell Sage Foundation brought to RAC new collections of institutions that had significant programmatic overlap with existing collections. This was particularly true for medical research, medical education, public health and health care policy in the case of Commonwealth, and in social welfare, economics and policy planning for Russell Sage.

These additions began a new chapter in the history of the institution, and in essence placed a different emphasis on what the name, Rockefeller Archive Center, actually means. Others that have joined us over the years include the Foundation for Child Development, the Lucille Markey Charitable Trust, the William T. Grant Foundation and the John A. Harford Foundation.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

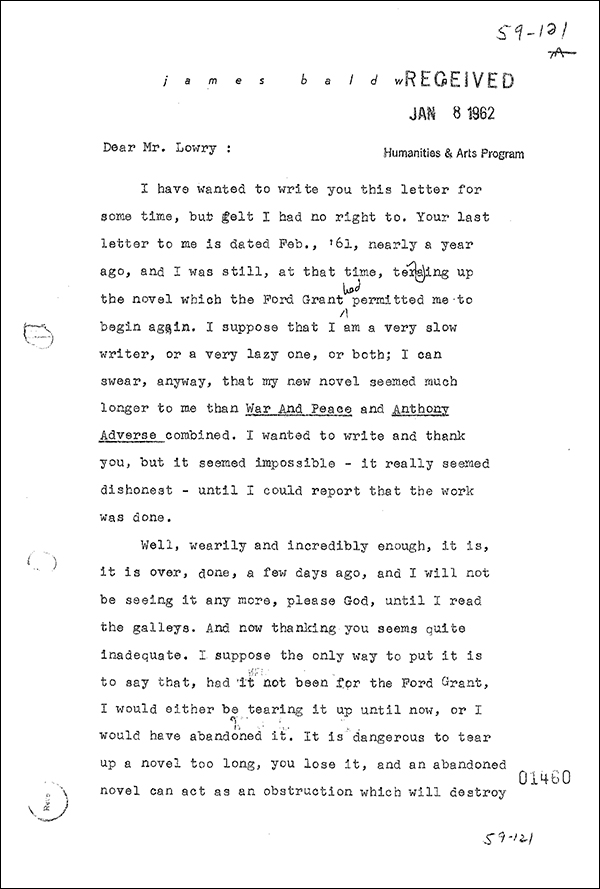

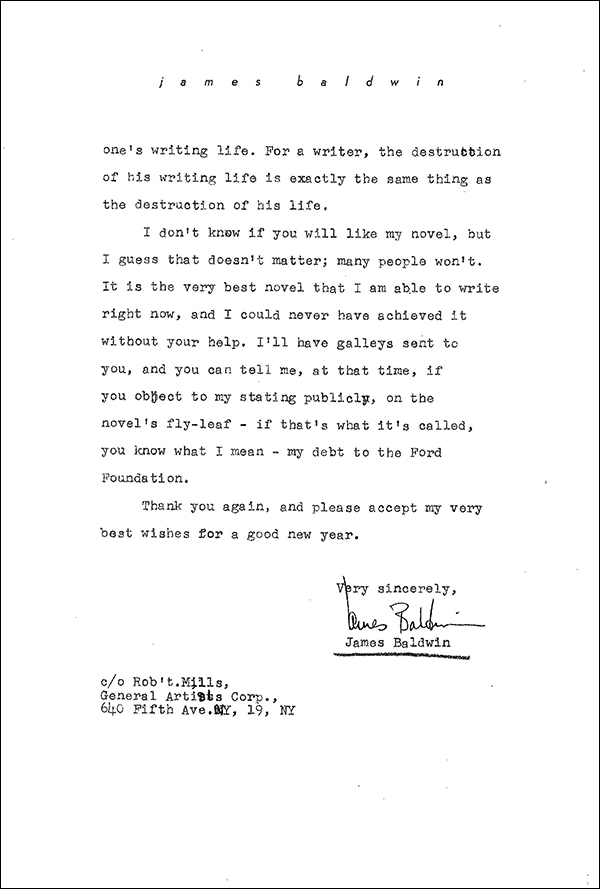

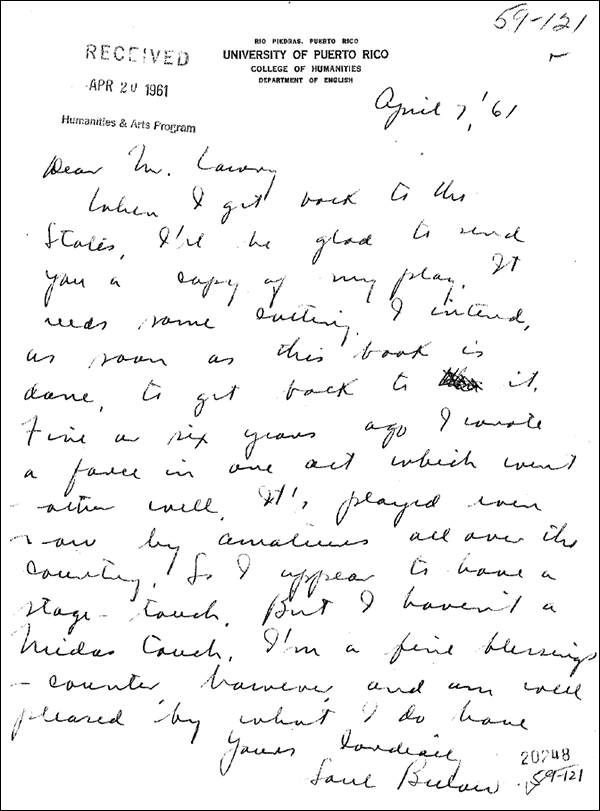

Some documents in the archives need little explanation. Here, the authors James Baldwin and Saul Bellow write to W. McNeil Lowry, long-time vice president of the Foundation whose support of the arts made Ford one of the major contributors to the development of the arts in this country. Baldwin is referring, apparently, to his novel Another Country and Bellow may be referring to his play The Last Analysis.

Then, in 2011, we acquired the Ford Foundation Archives, the strongest statement yet of the new direction of the enhanced Rockefeller Archive Center.

The absorption of this material into our holdings was on a different order of magnitude from past accretions. While the archives of other foundations typically added a few dozen to a few hundred cubic feet of records (imagine a standard storage carton as one cubic foot), the Ford Foundation Archives involved taking in more than 2,000 cubic feet of paper records, 11,000 reels of grants stored on microfilm, and more than 200 cubic feet of audio-visual materials.

Once the collection was opened in the spring of 2012, the number of researchers who have come to use this archives has been extremely impressive. The vast majority are not writing about the Ford Foundation per se but studying the impact of Ford’s activities in the context of broader research. Scholars studying tropical agricultural innovation, rural development and civil society immerse themselves in the records of both the Ford Foundation and other archives here.

Our records of Ford’s role supporting reproductive research and family planning, academic freedom, transnational programs for peace and the fight for human rights domestically and internationally are all magnets for researchers to come to the Center.

Many scholars find that while their initial goal might have been to explore the records of one particular collection, such as the Social Science Research Council or the Taconic Foundation or the Near East Foundation on a given subject, they quickly discover that the Ford collection proves to be a fountain of valuable material for their study as well.

How does one measure the impact of an archive on knowledge? How can one quantify that and make any evaluation of the impact of the Rockefeller Archive Center on learning, on scholarship and, in essence, on the right for access to information? There are very few metrics to turn to. We do tap into twenty-first century technology and use Google Analytics to see the number of times we get “hits” on our website and, perhaps more important, of individuals who explore the “online finding aids” (the archival term we use for catalogues) to our collections. For example, last year, for the Ford Foundation finding aids alone, there were more than 15,000 Google-driven searches, representing users from all six continents.

As a more traditional example of the impact of our collections over the past 40 years, though, more than 6,000 books, dissertations, academic articles and conference papers have been listed in the RAC Bibliography of Scholarship, reflecting research that cites our materials. A few examples of the most recent Ford-related additions to our bibliographic database include an article in Portuguese on the role of the Ford Foundation in developing the social sciences in Brazil, a report of Ford support for symphony orchestras, an article on Black power in the postmodern city, an article in German on agricultural development in East Germany, and a conference paper on American foundations and cultural diplomacy in Italy during the postwar period.

As more researchers learn about our Ford Foundation collections from citations, from colleagues and from internet searches, we expect that this trend of heavy use of our collections will not only continue but will grow in size and breadth.

The Rockefeller Archive Center, the Ford Foundation and the people connected with both institutions have a clear reason to cheer these developments—and we are certain Martha Baird Rockefeller would approve what we have done with her home.

More information about the Rockefeller Archive Center, and about the possibility of donating official and personal papers to it, is available by contacting Lee Hiltzik at lhiltzik@rockarch.org.

|