NEWSLETTER

|

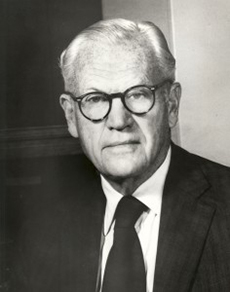

Remembering Trustee J. Irwin Miller By Willard J. Hertz

As a youngster in Columbus, Miller aspired to be a concert violinist and, as the owner of a Stradivarius, continued playing for friends and family all his life. After graduating from Yale in 1934, however, he was lured into the Diesel-engine manufacturing business started in 1919 by his uncle, Clessie Cummins, a local mechanic.

After serving in World War II as a navy lieutenant in the South Pacific, Miller became executive vice president of Cummins, then president and, finally, chairman, serving in that capacity until his retirement in 1977. He had built Cummins into the diesel-industry leader, with more than half of the heavy-duty truck market and an assembly plant in Scotland to serve Europe.

A close second to Cummins in Miller’s priorities was the beautification of his home town. He established and funded the Cummins Foundation to subsidize the architectural services for public buildings by leading or promising young architects and engineers. The plan was initiated with public schools and was so successful that the foundation offered it to other non-profit and civic organizations. Inspired by Miller’s leadership, leading architects were engaged with private funding for churches, homes and commercial buildings.

Over the years, consequently, this small Midwestern city became the site of buildings by a “who’s who” of contemporary architects including Eero Saarinen, Eliel Saarinen, Robert Venturi, I. M. Pei, Kevin Roche, Richard Meier, Harry Weese, César Pelli, Gunnar Bickerts and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Seven buildings built between 1942 and 1965 are National Historic Landmarks.

Miller supplemented a number of architectural projects with funds for outdoor sculpture. The most photographed scene in Columbus is a work by the great British sculptor Henry Moore in front of the foundation-designed public library.

Miller died in 2004, but Columbus continues as a “museum” of contemporary architecture and outdoor art with 60 sites. Each year Columbus attracts hundreds of camera-carrying tourists and bus loads of architectural students. This year, moreover, it is host to “Exhibit Columbus”, featuring 18 projects by designers from as far as Copenhagen.

Miller became a national figure in 1950 when he was instrumental in the establishment of the National Council of Churches and later served as its first lay president. He chaired the NCC’s Commission on Religion and Race, which coordinated organized religion’s support for civil rights legislation and jointly sponsored Martin Luther King’s March on Washington.

In 1962 Miller was elected to the board of the Ford Foundation, serving until 1974. I got to know him as Assistant Secretary of the foundation with responsibility for board meeting arrangements. As the keeper of the minutes, moreover, I attended all board meetings and was able to witness Miller in action.

Reflecting his life experience in Columbus, Miller became the board’s leading spokesman for grants in the humanities and the arts. At the time, under the leadership of vice president W. McNeil Lowry, Ford was greatly expanding its arts program and becoming America’s largest nongovernmental arts patron. Miller supported this effort at the board level, and he and Lowry became a powerful team.

Ford was the first foundation to support the dance, in 1963 making grants totaling more than $7.7 million to eight ballet companies, including the New York City Ballet and its affiliated School of American Ballet. Subsequent grants in the arts included $80 million to symphony orchestras, $3.4 million to the Dance Theatre of Harlem, $17.7 million to resident theaters around the country, and $13.6 million to regional ballet companies.

In 1974, as a farewell gesture, Miller invited the Ford board to hold one of its quarterly meetings in Columbus to see what he had accomplished in his home town. It was the first Ford board meeting outside New York City. I was sent to Columbus to assess and assure the conference, housing, food and local transport facilities needed for the meeting. This meant the care and feeding of 15 board members and their spouses, five vice presidents and a dozen or so other staff members.

I found the conference facilities in the Cummins headquarters building luxurious, with plenty of telephones for board members to stay in touch with their home offices. I also sampled the epicurean food to be prepared by two professional chefs on Miller’s personal payroll, a husband-and-wife team trained in Paris. While there were few taxicabs in Columbus, I found deluxe limousines available from rental agencies in nearby Indianapolis.

In a city offering the best in architecture, however, there was no hotel—only motel accommodations on the nearby interstate. The only motel large enough to accommodate the foundation visitors featured architecture and furnishings in tasteless 1890s style. This generated negative comments from some board members and their wives who were used to deluxe hotel accommodations in New York City.

Miller’s final contribution to the Foundation was to recommend Franklin Thomas, then president of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation in Brooklyn and a member of the Cummins board, as his successor on the Ford board. It was at his final board meeting in 1974 that Miller introduced Thomas to his colleagues. Five years later, Thomas was elected Foundation president.

|

Comments (1) |

| David Bonbright 9/15/2017 7:25:28 AM Thanks Will. Wonderful to read this. Irwin Miller was active in and around FF in the mid 1980s when I was there and I had several occasions to talk with him at length around the work of what was know as the Thomas Commission on South Africa. He had a way with words, as they say. One phrase I remember, certainly not precisely, was "History is the sound of hobnailed boots coming up the stairs as slippered feet come down." |