NEWSLETTER

|

The Early Years of The Moscow Office By Mary McAuley

The Ford Foundation had long supported activities relating to Russia but, in 1991, it established a grant-making program for organizations and institutions working in Russia itself.

Shepard Forman headed the program, which focused on support for the social sciences, legal reform and human rights. The majority of the grantees were Russian organizations, some well-established, some very new.

Joseph Schull was the program officer when, in 1995, a decision was made to open a field office in Moscow. What was it like to set up and run the new Moscow office in the turbulent years at the end of the twentieth century? And how did the Foundation meet the challenges?

There are strange gaps in my memory but maybe my telling will prompt others to fill them in. One day, perhaps, the archives will reveal much more.

Finding and setting up the office

On joining the Foundation as the new Representative in September 1995, I spent three months in New York, then traveling, first to Rio de Janeiro and Santiago to learn how a Representative’s office worked and then to Moscow with Shep, Joe and Jim Lapple to meet grantees, find an office and rent an apartment.

On the flight to Santiago not only did the elegantly dressed gentleman in the neighboring seat say, “I see you work for the Ford Foundation. As a graduate student I received a Ford Foundation grant”, but even at passport control an official said, “Ford Foundation, I know the Ford Foundation….” And in Moscow, at the words “Ford Foundation” the doors of Baker and Mackenzie, Price Waterhouse and Citibank seemed to fly open.

We were already registered as a charitable foundation with the new Chamber of Commerce in Moscow, which made it possible for grantees to receive grants from New York directly into their bank accounts and to respond to the tax authorities. But now we had resident status and needed to find an office.

Moscow was awash with new construction. Shep, Joe and I donned hardhats and clambered over building sites. We settled on a large building, undergoing reconstruction, on Tverskaya Street, right in the center, just ten minutes walk from Red Square. The Carnegie Corporation had its eyes on the top floor.

Meanwhile I found an apartment within walking distance of Tverskaya, on Patriarch’s Pond. “It’s not really large enough for a representative,” said Jim Lapple, but when I insisted he rang the young estate agent, told him to cancel his evening engagement and to meet him to sign the contract. That was the way Jim did things.

By the beginning of January I was in Moscow with my husband, Alastair, who had taken academic leave and would be teaching at the New Economic School. He spoke good Russian. The apartment had only a put-you-up bed, and a table and chairs, but someone found someone with a lorry to bring furniture from my flat in St Petersburg. Olga Lobova (assigned to me by Joe) and her husband, Ilya, had a car. They took us to one of few shops stocking china, glass and cutlery, then to a sale of Italian table lamps in a primary school and, lo and behold, we found a double bed in a Scandinavian shop. Jim Lapple authorized the order of a dining room table and chairs and arm chairs from Europe. Our children and friends from the United Kingdom, America and St Petersburg all came over the years to stay.

Olga was my assistant during those early months, and became our office manager when we moved into Tverskaya. But that would not be until June. For now the “office” operated out of two rooms and four armchairs on the third-floor landing of a hotel built in Moscow for the 1980 Olympics. Soon we recruited two program officers, Anne Stewart-Hill for higher education and Chris Kedzie for civil society, while I took responsibility for human rights and legal reform.

We also had two drivers and a temporary secretary. There was no local public transport within easy reach so we bought four cars—a Volvo station wagon, in which our chief driver came to pick me up each morning from Patriarch’s Pond, and three sedans. Anne and Chris, also renting apartments, drove their sedans themselves. We had four laptops, until one was stolen, and a printer. We used the hotel telephone system.

The loss of a laptop meant that, for a while, we had to share. One morning Sergei, our driver, drove me to the new gated community, surrounded by a high fence, where Anne lived. We parked and he leaped out and went to collect the laptop. I sat and waited…and waited…until, increasingly anxious, I went to the gate-keeper and asked if I could phone her apartment. “Sergei collected the laptop twenty minutes ago,” Anne said. I ran to the staircase. Laptops were very valuable and crime was rampant. Would I find his corpse on the stairs? I buzzed the lift. Then, oh the relief as I heard a faint voice: “Mary, I am stuck in the lift, can you get me out?”

Joe Schull came to introduce me to grantees and help interview prospective staff. We found an excellent candidate for grants administrator, Irina Korzheva, from the Institute for USA and Canada, but the runner-up, young Maria Chertok, a sociologist, was good too. “We’ll ask New York to let you have her as program assistant,” said Joe, and the deal was done. Maria stayed with us for a year, helping me with Anne’s portfolio when she went on maternity leave, and then moved on to Charities Aid Foundation, where she rose to become director.

And that brings me to what we might call “philanthropy in Russia in the nineties”. The state, its enterprises and institutions, had been responsible for the welfare of its citizens in the Soviet Union. Now, in post-perestroika Russia, with the economy barely functioning and wild privatization, western funding, both private and government, made its appearance to support science and education, institutes, medicine and law, homeless children, refugees, the new human rights or civil society organizations, the arts.…

By 1996, when Ford opened its office, the MacArthur and Soros foundations were already there, as were German foundations (Heinrich Boll, Adenauer, Ebert), the French and Dutch, Charities Aid Foundation from the UK, Fulbright under the Institute for International Education, and the British Council. The Council of Europe and some of the embassies also had grant programs, For example, the British Know How Fund, while the Eurasia Foundation was American-government money.

It was a confusing world for potential grantees and for donors themselves. MacArthur and Soros (Open Society) were our closest and most helpful partners in those early years. By the end of the nineties, the Russian oligarchs were into philanthropy: Potanin, Deripska and Khodorkovsky, to mention a few, had set up foundations. By then we had a Donors’ Forum, where all would meet at intervals, to exchange information. The idea for this had come from Barry Gaberman, and Chris Kedzie was instrumental in setting it up once we had a functioning office.

The renovations took about six months, and here Jim Lapple reigned supreme. I listened, entranced, as he pulled to pieces proposals and estimates from American and German building firms. Once when, in desperation, a building contractor had finally agreed to a proposal, Jim smiled encouragingly and said, “Well, cut it by a further fifty percent and I think we have a deal.” He remained unmoved by any of their pleas. Could I do the same?

In one situation we needed afire-safety certificate to have the finished work accepted. Alas, said the contractor, the fire service told them it was not happy with the paint they had used but that if they would redecorate the inside of the fire station, perhaps…. I must play Jim Lapple, I realized. “That is your problem,” I said, “and you must sort it out. I want the fire-safety certificate before I sign off on the terms we agreed to, and soon.” Did the fire station get redecorated? I never knew, but our walls stayed as they were and we got our fire-safety certificate.

The office on Tverskaya, and its opening

By June 1996 we were in our new office, open from 9:30 to 5:30, Monday to Friday, and by September had a full staff. This consisted of three program staff, a program assistant, two secretaries, a receptionist, two grants administrators, a cook, two accountants and two drivers. Jim Lapple had helped order office furniture—from Germany or Finland—and authorized the purchase of a computer system, a fax and a Xerox machine. Initially Xerox played the role of internet. Elena Ivanova, my secretary, would stand for hours printing papers for everyone.

A problem, seemingly unsolvable, arose over the office furniture. Large trucks were allowed to deliver in central Moscow only on Sundays, and I had gone into the office to receive and sign for a shipment. Alas, I did not notice that I had signed for two refrigerators instead of one. Any such purchases had to be registered, with date of purchase, with the tax inspectorate and remain on the premises. So what should we do? How could we get rid of a refrigerator we did not have? After fruitless discussions, we decided that a personal visit to the tax inspectorate by our now heavily pregnant office manager, Olga, and myself, playing the ignorant and anxious foreigner, was the best we could do. We threw ourselves on his mercy, and he agreed to change the document.

Felix Yakubson, a filmmaker and friend from St Petersburg, helped to buy pictures and made a video when Susan Berresford, then president of the Foundation, came from New York. Two short-term program assistants, Miriam Aukerman from the Foundation in New York and Rose Glickman, a historian and friend, helped in the early months. In 1997 we acquired mobile phones for program and key office administrators. Yes, they were large and heavy, but a real bonus. Mobile networks were spreading across Russia, and we had a lot of traveling to do if the Ford program was to reach out to the regions.

When Maria Chertok left us, we hired Dmitri Shabelnikov, a very able linguist then retraining as a lawyer, as my program assistant. I was struggling to run the office, build my portfolio on human rights and legal reform, and travel to grantees across the huge country. And there were visits to New York to fit in.

Susan Berresford came for the official opening of the office in June 1997. Elena Ivanova, on meeting her at the airport, was shocked by the small size and broken handle of her suitcase. “I just can’t find the time to buy a new one,” explained Susan. Both grantees and office staff warmed to her.

We arranged that the opening should be celebrated with a special performance of Die Fledermaus (which now included a reference, and a toast, to the Ford Foundation) by the new Gelikon Opera company. All the grantees were invited, speeches were made and vodka, gherkins and a cold buffet provided. It was fun. Celebrating is a national pastime in Russia.

Whom, I asked Susan, would she like to meet? Artists, musicians, professors, lawyers? She opted for the arts. I consulted with Alexei Simonov, himself a film director but now a grantee, founder of a “glasnost”, or media, NGO. We hosted a dinner at the House of Writers restaurant with guests Simonov, one of Russia’s leading pianists (who spoke good English) and the woman director of the Sovremennik theater. I put the pianist opposite Susan, with myself on his right and Alexei on her left, opposite me.

“Tell me, Nikolai,” said Susan to the pianist, “what is the main problem facing the world of music at the moment in Russia?” “Oh,” he replied, with an expansive gesture, “without a doubt it’s that there are so many homosexuals”. Simonov and I exchanged a glance of utter dismay and looked down at our plates. “Oh, no,” I thought. But Susan rose to the occasion. “It is interesting to hear you say that,” she said, without any change in tone. “Can you explain to me why that is a problem?” To my shame, I don’t remember the rest of the conversation, but we kept our Arts funding.

Office life, cars, computers—and surveillance?

I don’t remember the size of the office budget as opposed to the grant budget. It would be interesting to know how the “costs” of the field offices have varied over time. I always felt that, given the amount of paper work demanded by the Russian authorities, we must have been an expensive office in terms of staff costs. Or not? It was always interesting to visit another field office and try to sense common and unique features but I never felt sure I knew.

We had a kitchen and a cook, Nadya, who designed the lunch menu, collected lunch money from us all on a Monday, bought the food and prepared the meal. Visitors from New York paid into the kitty. Barry Gaberman, probably our favorite visitor, always praised Nadya’s cooking as the best he ate in any Foundation office.

Life was rarely dull in the office. “The women from the Caspian will be here, with caviar, at 2 p.m.” a message flashed on my screen. And there they were, two stout women with their wares: black caviar in plastic containers, 500 gr or a kilo. Black caviar had gone from the shops but still made it to Moscow. I can’t remember what it cost but it was very little. And it kept for an age in the fridge. I think I bought a kilo.

After more than a year, maybe two, we received a notice that our cars had never been properly registered as they crossed the frontier. We should now pay to have them sent to Finland, registered and returned to us. Dima, our chief driver who loved the Volvo, was outraged. This was all a set-up, he declared. And, indeed, while we paid some money and got some new papers, the cars (according to our drivers) sat, freezing in the winter weather in a yard on the outskirts of Moscow.

Dima was a driver from heaven who, in silent concentration, could get me to the airport through the worst traffic. We would skim through roadside parking lots, fly over or through underpasses and then, as the road to the airport opened, with the speedometer reaching 120, we would be there, with just enough time for me to make my flight. Sometimes I was tempted to cut the time short, just for the experience.

Chris Kedzie, our program officer, originally a fighter pilot until he lost a leg to cancer, knew how to respond to the traffic police who would sometimes stop a car with foreign plates. Flagged down, he would be out of the car, standing, holding all the documents, before the policeman had time to turn around and see that Chris had but one leg. With dismay and incredulity the officer would wave Chris back into the car and on his way.

Our computers were wonderful. In the early nineties I had met a young computer-wizard in St Petersburg, the son of a friend, a boy who had built his own computer. By 1996 he was working in Moscow for Sberbank, the government savings bank. He became our computer specialist, working weekends and some evenings. He advised what to buy, maintained and updated the equipment, and sorted out the problems. I was very proud. He was surely the best computer specialist in all the Foundation.

Years later, sitting in London in despair in front of a computer that no one was able to get to work properly, I emailed: “Anton, please come.” He came, and together we went to PC World, where he told them the extra things he needed, set it all up and left the computer running while he and his girlfriend went to the Design Museum. Next morning he pronounced it in good working order and they left for Moscow. It worked for years.

Was the office bugged? Our telephones? Who knows? All our activities were legal but there was the odd occasion when it was best to talk, maybe on a landing or in the street. One of our young staff was requested to come for a conversation with the FSB (security services). She wriggled out of it, insisting she had nothing to say of any interest, and the matter was dropped. One of our drivers was tricked into finding himself facing FSB officers across a table, and was scared. A conversation with an experienced Russian colleague provided some reassurance.

I had always assumed that among the office staff there was probably one who reported on office activities, although I found it hard to imagine who it might be. And all our visitors had to check in downstairs where, it was clear, the receptionists were security-trained.

Paying for things, inflation and the bank crash of 1998

Program officers had their salaries paid into Citibank in New York, and Foundation credit cards. We had a bank account with Bank Moskvy for staff salaries and office expenses. Program and office staff, their married partners and children up to the age of 18 had medical insurance paid by the Foundation. The choice of polyclinic was up to the individual. Hospital care was also covered (Elena Ivanova’s son found himself in the Kremlin hospital at the time that Russia’s president, Boris Yeltsin, died there). Costs were covered for children born to both program and office staff during these years. Coverage continued for office staff for a year after the Moscow office’s closure, and for program staff when they left. That was pretty remarkable.

Was rent for the Moscow office paid monthly or quarterly from New York to the Russian company that owned the building? And was rent for the apartments paid directly from New York? I suspect so. How did we pay for heating and lighting? I am not sure. Our office costs must have included telephone, fax, internet, mobiles and, of course, travel. Tickets, train or air, were booked through a travel agency. Any other expenses, for example, entertaining a grantee or visitor or Foundation officer, which couldn’t be paid for with a Foundation credit card, were reclaimed by handing in the receipts to my secretary, Elena Ivanova, who kept a small amount of ready cash in her desk drawer for these expenses as well as for plants, petrol, office stationery, postage, couriers, etc., and getting them signed for. Once a month she reported to the accountant, Elena Petukhova. We sent each week, by courier, a large package to New York that contained our grant applications, reports of all kinds, three typed copies of travel authorizations, reports by the accountant, etc., and received a package in return.

Did we pay bribes? What kind of bribes? To policemen who stopped our cars? To banking, tax, accountancy officials? Not to the best of my knowledge, but sometimes an accountant or office manager would set out somewhere with a box of chocolates.

Bruce Stuckey, the Foundation’s Director of Human Resources, advised on contracts. Was it Bruce, or perhaps Buzz Tenny or maybe Linda Strumpf, who authorized the steady increase in staff salaries as inflation in Moscow started to rocket upwards in 1997-98? It was a nightmare, poring over salary scales and dollar/ruble rates, making adjustments and trying to reassure office staff that I would do all that I could. Then, in August 1998, came the crash. The government defaulted on its debts, banks closed or ceased trading, the stock market plummeted and the ruble lost its value against the dollar. Most banks, including Bank Moskvy, shut down.

How could I pay the office staff? How could grantees pay for their ongoing projects? I don’t have clear memories of how the office coped. We must have opened an account in the still operating government Savings Bank. I remember running with our driver, Sergei, through the underpass beneath the square on Tverskaya, both of us carrying two holdalls full of ruble notes to get them to Sberbank before it closed for lunch. But where did we get the rubles from? And did we subsequently move all accounts from Bank Moskvy to Citibank?

Many projects simply went on hold for a month or two. But preparations for a workshop on prosecutors’ strategies to combat corruption in the United States and in Russia, organized by the Procurator’s office in St Petersburg with the Vera Institute of Justice in New York, were already underway. The Procurator’s office was to pay the costs and the fares for the procurators who were coming from across Russia but it could not access the money in its bank account. What to do?

I asked the Vera team to bring dollars in cash from their personal accounts, and I asked Bruce Stuckey, who was coming separately to bolster the morale of our office staff, to bring as many dollars as he could. I then took a packet to St Petersburg and, very nervous, met the senior procurator in a hotel lobby. “Don’t worry, Mary,” he said, as he transferred the packet to an inside pocket, “I am a trained operative.”

Spread across Russia, celebrating five years, and my fellow reps

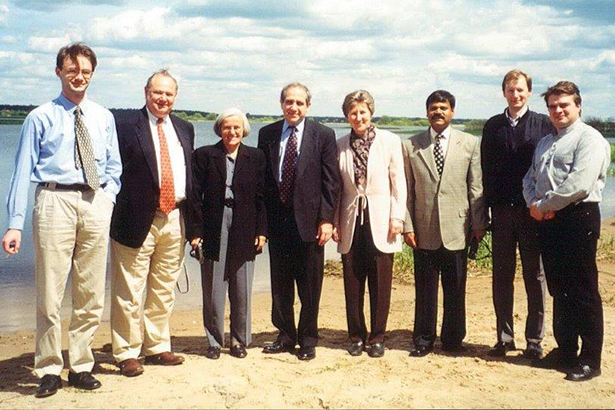

Visits from New York were events. Barry Gaberman came more than once. As did Buzz Tenny. There are photographs of them at an office picnic in the countryside outside Moscow, where some of us swam in the river, and on a boat, returning, still drinking vodka. Mizanur Rakhman, a Ford grantee from Bangladesh, a lawyer who had studied at Moscow University and was now acting as a consultant to some of our grantees, is there too. Was this in 2001 when we celebrated our five years as an office?

By now we had four program officers: myself (human rights and legal reform), Galina Rakhmanova (higher education in the social sciences), Irina Iurna (media and the arts) and Chris Kedzie (civil society). The grant budget had risen to perhaps $12 million per year, and we would bid for, and get, extra funding. For example, the Foundation funded the purchase of a building by the Memorial Society after a visit by vice-presidents Brad Smith and Alison Bernstein.

Our grantees were spread across the country, and one of our rules was that program officers must visit and see a grantee in action. But Russia is a huge country, and so we made no direct grants in the Far East. And there was a war on in Chechnya. We relied on tried and tested organizations, based in Moscow or other key cities, that worked with small organizations in faraway or dangerous places, to do what they could.

But we still traveled far and wide. On one occasion, sitting miserably in a very cold airport at six in the morning in the Urals, I wondered why, oh why, did airline tickets always give flight departures in Moscow rather than in the local time? I had three hours to wait.

Not only Susan Berresford and Alison Bernstein came to our five-year celebration but also several of the Foundation’s trustees. Carl Weisbrod had already made a visit, but perhaps this was the occasion when Henry Shacht came. We rented the grand Foyer of the Historical Museum on Red Square, with a balcony for the speakers and plenty of drink and a buffet. The visit required much planning, especially given that we then took Susan and the trustees to St. Petersburg. On the train? I find it hard to believe.

They stayed in the Grand Hotel Europa. We booked a room for lunch in the Literary Café where Pushkin ate his last meal before departing for the fatal duel. I read a piece on his famous poem “The Bronze Horseman” from Marshall Berman’s “All that is solid melts…” and an actor recited the poem. Then it was off to the Hermitage, to a reception in its theater. But first we gathered in one of the galleries for a demonstration by hefty workmen who, even with a pick axe, could not shatter the new glass that had been installed, with a Foundation grant, to save the pictures from too much light. Some of the party lost its way hurrying down from the Impressionists. “No need for concern,” said Richard West, Director of the National Museum of the American Indian and a Ford trustee, “an American Indian can orientate himself wherever he is. Follow me.” And we did.

Joe Schull, who left the Foundation in 1998, had stressed that the visits of senior Foundation staff and trustees must go smoothly (“Check,” he said, “if you take them to a restaurant, that there’s toilet paper in the washrooms.” How, I thought, am I expected to do that?) and that their status be properly recognized. I am not sure that I always got this right. Had I really allowed Lena Ivanova and Irina Korzheva, our grants administrator, and Sergei, our driver, to take Susan Berresford to visit a famous monastery outside Moscow on their own, came a polite query from New York? And had I let our two Russian program officers take sole responsibility for a visit to St. Petersburg by the two vice presidents to meet grantees?

It continued to surprise me how deferential to authority even the program staff in the Foundation were. But then this was something I had become aware of in the American academic community. Americans were uncomfortable if senior academics were criticized at an open meeting or seminar. “But Mary doesn’t mean…” someone would hurriedly interject, when it was precisely what I did mean. And it was the same at the Ford Foundation. An exception here was Joe Schull (did being a Canadian make a difference?) who, even as a graduate student, was outspoken, and Susan confirmed that there were times when she wanted to slap him for telling her what she ought to be doing.

My fellow reps were a great crowd. I loved visiting their offices or spending time with them at our meetings in New York, but “Now, she’s said it” I heard one of them whisper behind me at a meeting when we had decided that I should express our concern, firmly but politely, to the Foundation’s leadership.

I don’t want to make too much of this. The Foundation was a great institution to work for. Not only was it a very generous employer, but the support given to its staff in the setting up of an office was absolute. In time of need or in a crisis, Bruce Stuckey, Jim Lapple or Barry Gaberman responded immediately. We had the freedom to run the office in a way that made sense in local conditions. Approval of our grant-making strategy and of our grants (perhaps helped by Russia still being a little-known country) was always given. And there were truly remarkable individuals among its trustees and staff and the grantees we were privileged to support.

“Don’t cry,” said Sergei as he drove me, for the last time, to catch the plane back to London, adding, as he always did when the going got tough, “Victory is almost ours.”

But I still wept. This really was the end of an unforgettable seven years in Russia, and with the Ford Foundation.

Mary McAuley, who left a post at Oxford University to join the Foundation, now lives in London. Her book, Human Rights in Russia, published in 2015 by I.B. Tauris, includes references to Ford’s support for human rights. She wrote this article especially for the newsletter.

Ford in Eastern Europe: Lessons Unlearned by Irena Grudzińska Gross

|