NEWSLETTER

|

From LAFF’s Archive: Thinking About Doc

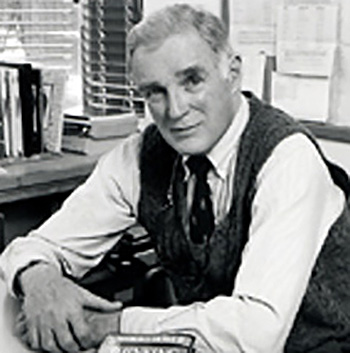

The Summer 1994 issue of LAFF’s newsletter ran excerpts from a book by the late Harold “Doc” Howe II, Thinking About Our Kids: An Agenda for American Education. Doc had been a Ford Foundation vice president from 1971 to 1981.

All of these skills I presumably had been taught a few months earlier at the Naval Mine Warfare School in Norfolk, Virginia. Like most new school teachers, I had learned the theory and not the practice and therefore dealt with reality the hard way, by making mistakes and correcting them. Fortunately, my mistakes did not prove fatal.

After many years of muddling about in schools, colleges and the public and private agencies that service them, I am still persuaded that the best way to learn about something is to do it. In fact, one of my strongest convictions about improving education is that we need to make better use of the power of experience in the learning process.

Other realms of experience, too, lie behind what this book has to say. One is personal. My family, and particularly my father, filled my early years with exposures to education that went beyond my own attendance at school and college. He was a Presbyterian minister, an all-American quarterback, a private school teacher, chaplain, administrator and coach, a conscientious objector in World War I, a college professor at Dartmouth, and for 12 years the president of a predominantly black private college in Virginia, Hampton Institute (now Hampton University).

This institution was founded in the mid-1860s by my maternal grandfather, a son of missionaries to Hawaii and the commander of a black regiment in the Civil War. He launched Hampton Institute while working for the Freedmen’s Bureau, the federal agency created to assist blacks with the transition from slavery to freedom. During my secondary school and college years, my family lived at Hampton—then an island of desegregated faculty and black students in a totally segregated society. This combination of forebears with a strong element of social conscience and exposure to life in the South before the Brown decision no doubt helped to shape my views about education and society….

In addition to rethinking our safety net for school readiness, we need to make better use of the incomplete collection of separate programs that now serve us for that purpose. Back in the 1970s, when I worked in the Ford Foundation, a colleague of mine, Terry Saario, thought that Ford should invest some of its funds in understanding the problems of youth and developing information about their needs that would assist both state and national governments to design better policies to save the young. To get started, she brought together a series of regional conferences, a cross-section of people from agencies serving children and youth. One thing we learned from the conferences was that a good many of the people working on behalf of the young in a given state had never met and were glad to have the opportunity at the Ford Foundation’s expense.

In at least one of these meetings, an effort was made to discuss the total annual budget for all of the activities for early adolescents in a particular state. As this information was laboriously assembled, the men and women present became more and more surprised by the vast amounts that were indeed available annually. The question was asked, “Suppose that instead of having each item on this list a totally separate endeavor, we were able to do more comprehensive planning to meet priorities of need: would the funds be spent as they now are?” The response was a resounding negative. There followed a long discussion of the political difficulties and the turf battles among agencies that would result from any such effort to coordinate funding for youth so that high-priority needs might get the attention they deserved.

This anecdote raises issues…about the need for more coherent planning and operation of services for all young people. This topic must stand at the top of our agenda for thinking about public funds for education broadly conceived. Unless we bring an end to the long-standing fragmentation of programs and funding, there is a good chance that the limited funds we have will be used for low-priority purposes.

|